tdm - Terraform for Test Data

tdm (short for Test Data Management) is an open-source library to help you manage your test data. You can think of it as a Terraform for Test Data: You define the state your test data should be in, and TDM interfaces with your data stores (e.g. your own APIs and/or third-party APIs) to get things into that desired state.

Usage

Installation

npm install test-data-management

Using tdm in your project

import { TDM } from "test-data-management"

// Define these yourself

import { users } from "./fixtures/users"

import { UserMapper } from "./users-mapper"

import { UserExecutor } from "./users-executor"

async function main(dryRun: boolean) {

const tdm = new TDM()

tdm.add(issues, new UserMapper(), new UserExecutor())

await tdm.run({ dryRun })

}

const args = process.argv.slice(2)

const dryRun = args[0] === 'false' ? false : true

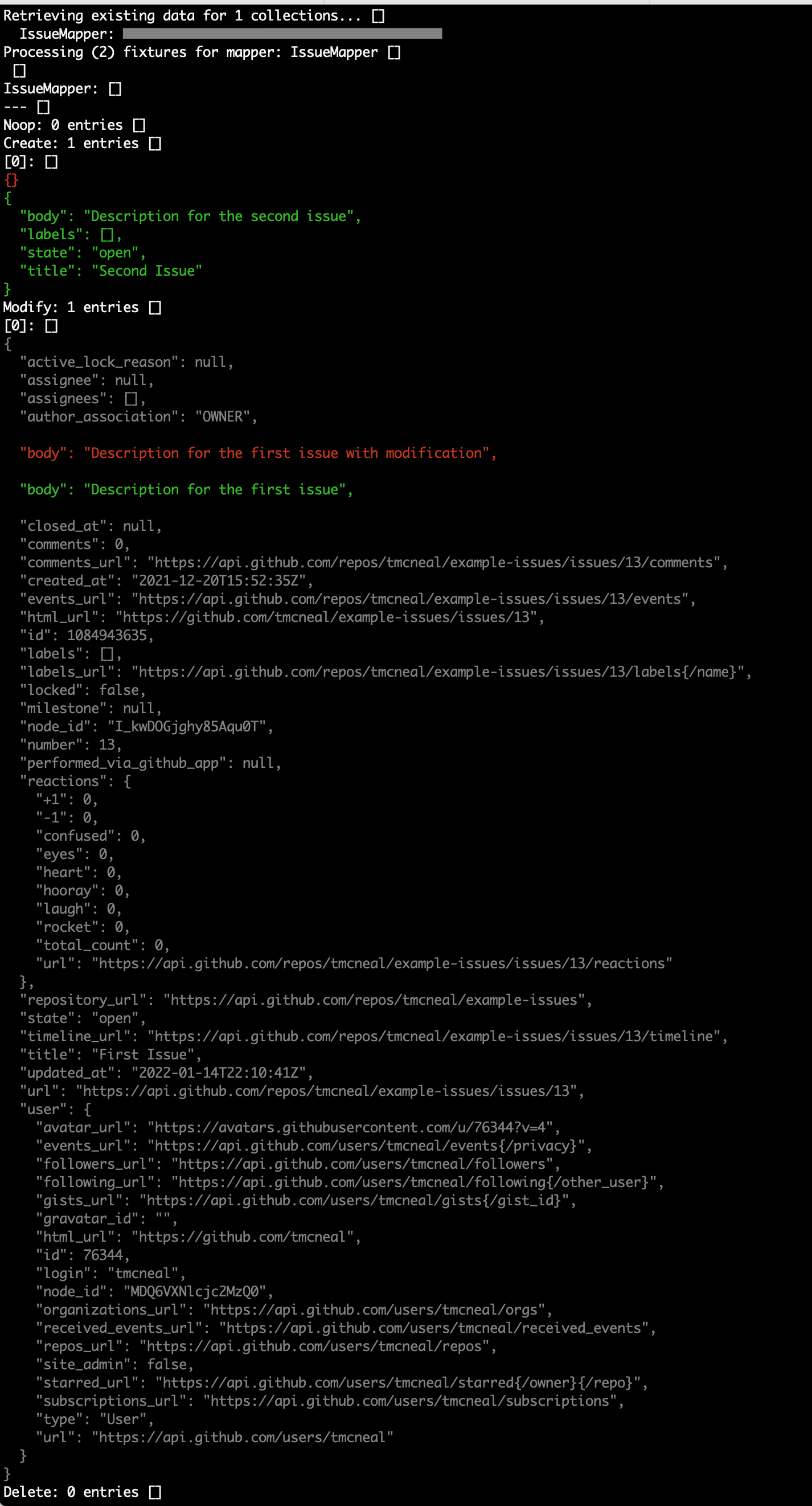

main(dryRun)When running TDM in dry-run mode (which is the default), you'll see what changes TDM would apply to get your test data into the expected state. Here's an example of what that looks like from our Github Issues example:

See the examples directory for some examples that you can run yourself.

Overview

When creating end-to-end tests, you'll often need to make assumptions about the state of the data in the system you're testing. These assumptions could be simple, like assuming you can sign-in using a specific username and password. But usually these assumptions are much more complex. Imagine you're testing the checkout process of a Shopify store. A single test of the checkout flow will end up making several big assumptions about your test environment, including:

- The product that the test is scripted to purchase must not only exist, but must have the correct product name, description, and other associated metadata.

- The product appears in search results and is assigned to the appropriate categories in the category hierarchy.

- The product is in-stock and has inventory available for a specific size and color.

- The correct shipping rates exist in the third-party shipping provider.

- The correct tax rates exist in the third-party tax provider.

- The payment gateway is set up to accept payments from a test card number.

To get the system into the proper state (in other words, to fulfill the assumptions above), you could write a set of SQL scripts to load this data, or maybe restore your database from a snapshot that's a known-good version of the system. In most cases you're likely not managing your data explicitly at all, but instead are setting it up once and hoping it doesn't change. The current approaches for actively managing test data are difficult to use and maintain, and lack support for handling third-party data (like the tax, shipping, and payment information in the checkout example above).

TDM is an alternative approach for managing test data that lets you manage first-party and third-party data as a set of fixtures in your codebase. These fixtures are strongly-typed, and the types can mostly be auto-generated based on the OpenAPI definitions of both internal and third-party APIs. Under the hood, TDM gets your data into the desired state by interacting with these existing internal and third-party APIs.

Concepts

Fixtures

Fixtures are objects used by TDM to collectively represent the desired state of your system. Unlike other tools which use configuration formats like JSON or YAML to represent fixtures, Fixtures in TDM are just Typescript objects. Using Typescript vs. something like JSON provides a few key benefits:

- You can take advantage of the structural typing features of Typescript to get compile-time type checking for situations that would normally be runtime error in other tools, such as defining a fixture without a populating a required field.

- Typescript's built-in Utility Types, like

Omit<T>andRequired<T>, combined with structural typing semantics mean you don't have to write much boilerplate code. - Fixtures are not constrained by whatever constructs are present (or not present) in your configuration schema. TDM fixtures have all the expressivity of a normal Typescript object. This means implementing things like randomly generated values or large amounts of synthetic data can be done in a few lines of code.

Entities and Mappers

Each Fixture is closely associated with an Entity, which is an object retrieved from either a first-party or third-party data store, and whose interface is defined by that data store. TDM provides first-class support for entities defined by an OpenAPI specification, however you can also define your own entities pulled from data stores such as GraphQL APIs and database tables.

Mappers define how to translate an Entity into a Fixture and vice-versa. If you've ever used an Object-Relational Mapping library (ORM), Mappers will look familiar.

Let's assume we want to define some fixtures representing the users who have accounts in the application we're testing. The API endpoint that returns a list of users in an account might use the following Interface to represent each user:

export interface User {

id: number,

email: string,

firstName: string,

lastName: string,

createdAt: number,

}When defining Fixtures representing this Entity, we don't want to define the id field explicitly. The id field is likely an internal identifier that by itself has no meaning, and we'd rather have the REST API auto-generate for us. The email, firstName, and lastName fields are relevant to our tests, so we'll define those explicitly in our fixtures. Lastly, the createdAt time isn't relevant to our tests, so we'd like to disregard it.

Here's how you'd define a Mapper that represents this desired behavior:

export class UserMapper extends Mapper<User> {

fields = {

id: Property.Identifier,

email: Property.Comparator,

firstName: Property.Field,

lastName: Property.Field,

createdAt: Property.Ignored,

} as const

}The Mapper defines each property in the Entity, assigning it one of the following property types:

-

Identifier: A property that represents the "primary key" of the entity. A good way to determine the identifier is to see which field is used to reference a resource in the collection in other related API endpoints. So for example, if another API endpoint

GET /users/:iduses theidfield to reference a single user within the list of users, thenidis your identifier. -

Comparator: This is the property you'll use to determine uniqueness in your fixtures. In the example above, we've specified

emailas a comparator since it uniquely identifies a user in the collection of users. In cases where a field should be both identifier AND comparator, give it the valueProperty.Comparator. - Field:: A property that is not an identifier or comparator, but is defined in the fixtures.

- Ignored: A property that is not defined in the fixtures.

With our Mapper defined, we can now write our fixtures:

export const users: Fixture<UserMapper, User> = [

{

email: 'john@example.com',

firstName: 'John',

lastName: 'Doe',

[Relation]: {},

},

{

email: 'jane@example.com',

firstName: 'Jane',

lastName: 'Doe',

[Relation]: {},

},

]With the Fixture type, you'll get proper type-hinting and transpilation errors for scenarios like forgetting to define a required property in a fixture, or defining a property value that is of the wrong type.

Fixture Relations

Often an entity will reference one or more other types of entities. Expanding on the example above, imagine the User entity contains an accountId which represents the account that the user belongs to. The details of that account can be retrieved using a separate endpoint in that same REST API. In a database schema, you'd normally model this as a foreign key relationship wherein the Users table has a foreign key (accountId) to the Accounts table.

When modelling this in a fixture, we don't want to store the accountId value itself since it lacks semantic meaning. TDM instead provides a special way of referencing these "foreign key" relationships using information that is semantically relevant, and preserves referential integrity within your fixtures:

export interface User {

id: number,

email: string,

firstName: string,

lastName: string,

createdAt: number,

accountId: number, // Reference to the 'Account' entity

}

export interface Account {

id: number,

name: string,

status: 'Active' | 'Inactive',

createdAt: string,

}

export class UserMapper<User> {

fields = {

id: Property.Identifier,

email: Property.Comparator,

firstName: Property.Field,

lastName: Property.Field,

createdAt: Property.Ignored,

accountId: {

mapper: new AccountMapper(),

field: 'id',

}

} as const

}

export class AccountMapper<Account> {

fields = {

id: Property.Identifier,

name: Property.Comparator,

status: Property.Field,

createdAt: Property.Ignored,

} as const

}

export const accounts: Fixture<AccountMapper, Account> = [

{

name: 'Example Account',

status: 'Active',

}

]

export const users: Fixture<UserMapper, User> = [

{

email: 'john@example.com',

firstName: 'John',

lastName: 'Doe',

[Relation]: {

accountId: { name: 'Example Account' },

},

},

{

email: 'jane@example.com',

firstName: 'Jane',

lastName: 'Doe',

[Relation]: {

accountId: { name: 'Example Account' },

},

},

]Properties inside [Relation] are references to other entities that are defined elsewhere. In order for TDM to resolve the reference, the Relation must define the comparator value(s) for that entity. In the example above, AccountMapper defines a single comparator name for the entity Account, thus the Relation in the user fixtures references the accounts using the name property.

Executors

Executors define the CRUD operations for each Fixture definition. So for the User example, the UserExecutor defines how to insert/select/update/delete rows into the table:

export class UserExecutor extends Executor<User> {

api: ExampleApi

constructor(api: SupabaseApi) {

super()

this.api = api

}

async create(obj: User): Promise<unknown> {

return this.api.createUser(obj)

}

async readAll(): Promise<User[]> {

return this.api.getUsers()

}

async update(obj: User): Promise<unknown> {

return await this.api.updateUser(obj.id, obj)

}

async delete(objOrId: User | number): Promise<unknown> {

const id = isUser(objOrId) ? objOrId.id : objOrId

return await this.api.deleteUser(id)

}

}

function isUser(objOrId: User | number): objOrId is User {

return (objOrId as User).id != undefined

}Since we need to know how to create/read/update/delete each type of Fixture, each Fixture definition must have it’s own corresponding Executor.

Generating entities using OpenAPI specifications

Entities can be generated from OpenAPI 3.x specifications by using the following command:

node dist/index.js generate <source-type> <source-url> <destination-folder>