Table of Contents generated with DocToc

- CXLTX Styles

CXLTX Styles

An incipient and hopefully sensible collection of basic XELATEX style sheets.

Pull Requests Are Awesome.

\usepackage{cxltx-style-base} % you always want this one

\usepackage{cxltx-style-cjk} % Chinese / Japanese / Korean

\usepackage{cxltx-style-accentbox} % boxed accents as per http://www.eutypon.gr/eutypon/pdf/e2000-05/e05-a04.pdf

\usepackage{cxltx-style-smashbox} % boxed contents to preserve lineheights

\usepackage{cxltx-style-multimulti} % multiple columns and rows on pages and in tables

\usepackage{cxltx-style-position-absolute} % absolute textpositioning

\usepackage{cxltx-style-pushraise} % shove and shift those glyphs

\usepackage{cxltx-style-stackedpushraise} % similar to the pushraise

\usepackage{cxltx-style-convert-to} % simplistic unit conversion

\usepackage{cxltx-style-equals} % equality testing made easy

\usepackage{cxltx-style-oddeven} % checking whether we're on an odd or an even page

\usepackage{cxltx-style-trm} % make a hundred colors glow (in terminal output)

\usepackage{cxltx-style-abspos} % store current (x,y)-position (in mm)Installation

Simply clone

git clone https://github.com/loveencounterflow/cxltx-styles.gitor download an archive to get the code.

To enable TeX to resolve \usepackage{cxltx-styles-*} commands, put a symlink to your

CXLTX Styles directory into a directory that is on LaTeX's search path. On OSX with TeX Live, that can

be achieved by doing

cd ~/Library/texmf/tex/latex

ln -s route/to/cxltx-styles cxltx-stylesIn a more general fashion, you may want to

kpsewhich -var-value=TEXMFHOMEthen take that route (e.g. /Users/$USER/Library/texmf) and append /tex/latex (which gets you

/Users/$USER/Library/texmf/tex/latex) to obtain a suitable location. It may be necessary to first create

that location using mkdir -p ~/texmf/tex/latex. Confusing it certainly is.

Badges

Each CXLTX Style has a particular 'badge', i.e. a prefix, prepended to each of the names defined in that

style. Badges are mostly two lowercase letters out of [a-z] that are reminiscent of the style's name.

All names of private members (which are not documented here; see the source) start with the sigil @,

followed by the badge, followed by the name proper. Further, all names are written out (no surprising abbr.

pls.) and use CamelCase (coz that dash is no-go in TeX, y'know).

Badges are necessitated by the fact that all of the huge ecosystem that is TeX & LaTeX lives within one single, enormous namespace. There's not even so much as a stringent convention to minimize chances of naming collisions. As a result, name and package option clashes are a frequently observed nuisance that any user of LaTeX has to put up with.

CXLTX Style: Position Absolute

CXLTX Position Absolute (PA) is based on

textpos. It is intended to make it

easy to position single lines of text on the page (much easier than using textpos directly), using

absolute coordinates that take the left edge, the center point, or the right edge of the baseline of the

text and the edges of the paper, the text area, or custom coordinates as reference points.

PA loads textpos as

\usepackage[absolute,overlay]{textpos}so all material will be absolutely positioned (rather than relative to the current point of insertion), and put on top of everything (?) else on the page.

The latter option has been chosen to ensure

pagegrids will not cover material typeset with Position Absolute.

PA uses the starred form of the textblock environment, \begin{textblock*}... \end{textblock*}, which

means that all dimensions must be given as lengths rather than pure numbers. I feel this is an

advantage, as (1) pure numbers are only meaningful as 'abstract lengths' when used in geometry, but not as

concrete lengths in the physical world; and (2) simple arithmetics in command arguments are only possible

with lengths, not with numbers (textpos uses calc).

The badge of this style is pa. PA defines the following items:

paOriginTo, paOriginToPaper, paOriginToText, and paOriginIs

These commands are all concerned with the origin (the reference point) of the measurements you will want to

give when using \paRight, \paCenter, or \paLeft (for which see below).

The most basic command is \paOriginTo, which you can use to set the origin absolutely; the measurements

given here are always in turn interpreted as being relative to the edge of the paper, so

\paOriginTo{20mm}{25mm}will set the reference point to 20mm to the right from the left edge and 25mm down from the top edge of the

paper. If your coordinates refer to the paper without any offset, you can, instead of \paOriginTo{0mm}{0mm},

simply say

\paOriginToPaperHowever, i anticipate that most of the time people will want to place their text lines relative to the current text extent, not the paper. This can be done by placing

\paOriginToTextsomewhere near the beginning of the document (or just leave it with the default settings).

Important: in case you want to use the default \paOriginToText setting, please

-

be aware that changing page layout in the middle of the document necessitates re-issuing

\paOriginToText. PA caches the positions of odd and even pages, respectively, and won't detect layout changes unless told to do so. -

bear in mind that since this option uses

changepage, LaTeX has to run at least twice before you get correct results. You're already used to this, right?

Lastly, there is \paOriginIs which is internally used to keep state; it will expand to one of text (the

default), paper, or some custom (20mm,25mm) (for the first example, above).

With these considerations out of the way, let's have a look at how to actually put stuff onto the page.

paLeft, paCenter, paRight, and paTopLeft

These are the basic commands to place printing material onto absolute positions; unlike their counterpart

in textpos (the textblock environment), each takes three regular arguments, namely, the x position,

the y position (growing from the top to the bottom), and the content of the box:

\pa〚Left|Center|Right|TopLeft〛{$x}{$y}{$text}This code:

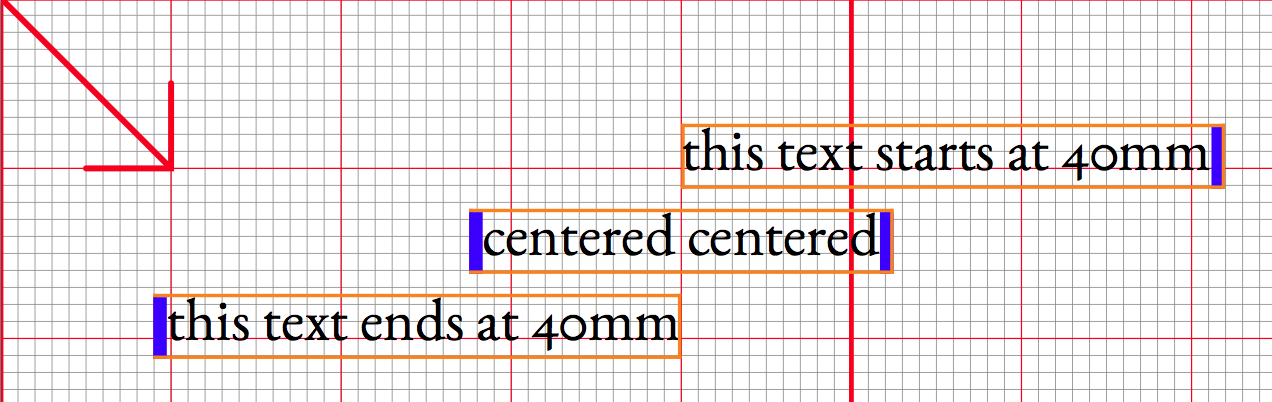

\paLeft{40mm}{10mm}{this text starts at 40mm}

\paCenter{40mm}{15mm}{centered centered}

\paRight{40mm}{20mm}{this text ends at 40mm}produces (with \usepackage[top-left]{pagegrid} and \paShow in the preamble):

The coordinate system origin and the direction of ascending values is indicated by the arrow; observe how each text box comes with one or two 'struts' (the blue bars) that regulate box heights.

You can also see that \paRight produces a text (the bottommost line) that is set flush right against the

x = 40mm vertical, while \paLeft text (the topmost one) is set flush left against the same; paCenter

centers the text horizontally so the 40mm mark lands smack in the middle. No surprises here, which is really

the purpose of this package! (The boxes and struts are only shown for demonstration; they're of course

absent from the output unless you state to \paShow them.)

The \paTopLeft command and its starred form, \paTopLeft*, are intended to be used when you want to

position material anchored at the top left corner. The unstarred form includes a strut (like the

commands discussed above); it is intended to be used with text. The starred form does not include a strut

and is intended to be used with images. Thus:

\paTopLeft*{10mm}{10mm}{\includegraphics[height=180mm]{/route/to/image.png}}

\paTopLeft{10mm}{10mm+180mm}{An interesting image.}will place an image with a height of 180mm onto the page, with a line of text right beneath it. Observe the simple math done here right in the macro argument; this may help to enhance readability and also introduces a way to store component lengths in variables.

paGauge

CXLTX Position Absolute promises to deliver text positioned with respect to the baseline of the text. Now

the baseline is a fickle thing that is different from font to font. There are two ways to get the baseline

right: either ask PA to do it for you, or else do it yourself. The easy way first: use \paGauge{...} like

\paGauge{abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyzABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ0123456789!?§\$}(using a suitable selection of characters) or simply

\paGaugeSample(which will use the sample shown above) in your document to have PA determine the (internal) dimensions

\@paStrutHeight, \@paStrutDepth, and the ratio

\@paHeightDepthRatio = \@paStrutHeight / ( \@paStrutHeight + \@paStrutDepth )Needless to say that you should make sure that both your character sample is representative and that the font that

\paGaugeimplicitly uses is the same that will appear in your positioned material.\paGaugedoes not produce any output.

Observe that while \usepackage{cxltx-style-position-absolute} will run paGaugeSample implicitly,

dimensions will at best be approximate in case you change fonts later in your document setup.

You may profit from using CXLTX Smashbox in case you want to mix characters from fonts with protruding heights and depths in your PA textboxes.

Now for the hard way: if you find you want to do it yourself (maybe because you're mixing typefaces on the positioned line), you're free to add something like

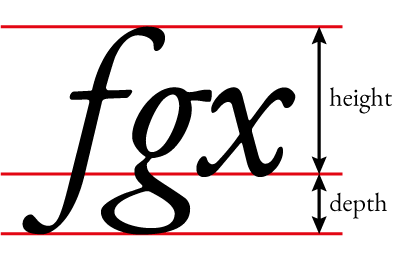

\paSetStrut{4mm}{3mm}which will both set the strut's height (the first argument) and depth (the second argument) and calculate the ratio as detailed above to find the baseline. This feature may prove useful for positioning characters from symbol fonts. For people who haven't heard of height and depth in type, here's a picture to clarify those concepts:

You can see that the 'height' is the length that a given text extends above the baseline (i.e. the one in

the middle) and the 'depth' is the length that it it extends below the same. Now textpos wants to know

the ratio of those with respect to the total height (that is, height + depth) to position its point of

reference, reckoned from the top—which is, of course, ratio = height / ( height + depth ).

Note To obtain a correct positioning of text boxes, only the relative height and depth of the strut

are important. Since material typeset with PA does not 'take space' on the page (i.e. it can overlap with

other material, just as a HTML <div/> with CSS style position: absolute would), the absolute height of

the struts (as long as it equal to or greater than the height and depth of any material within the box) is

of little consequence.—Which brings us to the next point.

paLeftGauge, paCenterGauge, paRightGauge

There are three convenience commands

\paLeftGauge{40mm}{10mm}{this text starts at 40mm}

\paCenterGauge{40mm}{15mm}{centered centered}

\paRightGauge{40mm}{20mm}{this text ends at 40mm}that work exactly like their counterparts without the ...Gauge suffix, except that they execute

\paGauge{#3} immediately prior to doing the positiong proper; furthermore, since gaugeing happens within

the confines of a TeX group, effects are kept local. These commands allow you to throw in materials set with

other typefaces and/or sizes without worrying much about typeface metrics. If it weren't for the quite

significant overhead and the incredibly log flooding incurred by the fp package, \paLeftGauge and

friends should be the default commands. When there is a lot of absolutely positioned material in your

document, be sure to make it so that the \paLeft commands get the main work to do.

Absolute Positioning and Page Breaks

As said in the preceding paragraph, material typeset with PA does not take space on the page—it may overlap

without triggering any line justification or word hyphenation action. Since this is so, it may also be the

case that while you know you did put printing stuff onto the page, TeX (rather, its output routines) may

be blithely unaware of that—which matters as soon as you have a page full of absolutely positioned material

and nothing else, and you want to use \newpage to advance to the next page.

Mind you, LaTeX in all its incredibly convoluted baroque / byzantine glory does care for you! It keeps you from comitting grave blunders such as emitting blank sheets of paper! I mean, you'd totally loose your street cred if that should ever happen to you, in the Data Center, with everyone and the staff looking at you, Waster of Computing Cycles! And Paper!!

I know i know. Anyhows, remember this: always use

\null\newpagewhen in doubt whether there was non-PA material on that page, but not in doubt that a new page is what you damn want.

There's probably a gazillion other methods documented how to get that new page but i like the non-chalant understatement of this particular incantation. I mean, null is nought is what i'm saying, right?—zilch, nuthin! We can put printing stuff on the page and TeX will think there's nil to print!, but when we explicitly tell TeX to send nada to output, then it will act like there was something to print...! Now i must stop at this or i'll get all worked up again.

paShow and paHide

You can use

\paShow

\paHiderespectively to show or hide the boxes and the struts that are used by PA. In case you want to muck with

their default appearances (boxes with slender, elegant outlines, whose creamy orange tint contrasts

gleefully with the sober marina blue of the rather sturdy struts that adorn each typeset line), refer to the

source.

Use \paShow and \usepackage[top-left]{pagegrid} to debug your PA-powered document today! Experience the

Beauty of Simplicity! Never look back to those inferior and clumsy methods of days gone by!

Enough of that.

CXLTX Style: PushRaise

CXLTX PushRaise (PR) provides (mainly) three commands to push a given glyph to the right (or the left) and to raise or to lower it, all in terms of the current font size and without taking up additional space:

龍覀龍,龍\prRaise{-0.125}{覀}龍

龍亻龍,龍\prPush{0.5}{亻}龍

龍。龍,龍\prPushRaise{0.5}{0.25}{。}龍Here is the output of the above, running XeLaTeX with xeCJK; the font is Sun-ExtA:

The image illustrates my use-case for these commands: to correct the positioning of glyph shapes in Chinese

fonts. It's a somewhat bad habit of modern CJK font designers that they shift those glyphs that represent

the positional variants of 'radicals' (such as 亻灬氵艹) to wherever they appear most of the time. This is

wrong and printed dictionaries normally don't do that, much less the 康熙字典 which was the first

major work to use the modern sytem of radicals. Looking at the examples above and comparing them with

fine printed matter, it also becomes obvious that 亻 is too narrow and 覀 is too flat—it should really look

like 西 with the vertical lines straightened. That, of course, cannot be fixed with prPushRaise, but at

least it's easy now to make the display less offending.

thx to werner @ http://tex.stackexchange.com/a/51115/28067 who provided the essentials for the

\prPushimplementation.

CXLTX Style: Transform

CXLTX Transform (TF) grew out of my new approach to defining formats

(to select font family, type size and so on) as LaTeX commands without text

arguments (call them 'environmental commands'), similar to the \color

command. In other words, where I would have written

Foo \fontA{\extraBig{bar}} bazbefore, I now write

Foo {\fontA\extraBig bar} bazusing groups instead of text arguments. Not only do I find this syntax somewhat cleaner; more importantly, it helps to avoid problems with expandability (key word 'robustness') glitches that TeX macros are so well known for. Also, using groups instead of arguments might cause less interference with line breaking.

One problem, however, is that I use CXLTX PushRaise extensively, mainly to

correct the placement of Chinese characters; now, PR is implemented using

commands like \raisebox—which of course needs a text argument that it sticks

in a box to push it around. This was when I asked, on

tex.stackexchange.com: Is it possible to

vertically shift the baseline without using a

box?

A very helpful Mr. David Carlisle was so friendly as to suggest a solution using LuaTeX's \pdfliteral:

Writing

x\pdfliteral{ 1 0 0 1 0 -2 cm}yputs some literal PostScript code into the PDF file that will cause the y and

any ensuing material to be lowered by 2 units. Just what I needed!

Delving deeper I found out the six numbers in front of the PDF cm command are

the elements of a 2D transformation matrix; more specifically, they are

responsible for

- x-scaling,

- x-skewing,

- y-skewing (not so sure about the last two),

- y-scaling,

- x-translation, and

- y-translation,

in that order. What's more, this stuff can be used in XeLaTeX as well, only the call convention is a bit different:

x\special{pdf:literal 1 0 0 1 0 -2 cm}yBecause these PDF literal calls effectively bypass TeX, whatever transformation

you apply will stay valid indefinitely; in particular, it will not get

automatically undone when a group ends. The main achievement of CXLTX Transform

lies exactly in this detail: all TF transformations that occur within a group

will be undone when the group ends. For example, transform-demo.tex has

this code:

\usepackage{cxltx-style-transform}

[...]

charm up down color strange\\

charm {\tfRaise{0.5}up} {\tfRaise{-0.5}down \tfPush{-1}color} strange\\

charm up down color strange\\When you look into the corresponding PDF, you will find that the three

occurrences of charm and the ones of strange all align horizontally and

vertically; only in the middle line, up and down are shifted up and down by

equal amounts; color is somewhat shifted to the left, but appears with the

same baseline shift as down.

Incidentally, this demonstrates that using

tfPushand\tfRaiseact a lot like CSSposition: relative; right: 0.5em; top: -0.5em;, except for the y-axis orientation: shifted characters do not affect the positioning of surrounding material; instead, the whitespace that was allotted for them stays in place and their shapes may overlap with other characters.

Implementation: The automatic undo facility has been implemented using

fifo-stack and the TeX

\aftergroup primitive; floating point arithmetic was kindly provided by the

venerable fp

package (yes,

TeX is one of those languages that give you a single global namespace filled

with gazillions of ultra-specific predefined words but needs external 3rd-party

libraries to do stacks(!) and sane multiplication(!!!)).

To be fair, stacks and floating point arithmetic has rather recently become part of the LaTeX3 interfaces; issue

texdoc l3fportexdoc interface3from the command line, which should open a PDF viewer with an extensive documentation of the available APIs, or go to http://ctan.mirrorcatalogs.com/macros/latex/contrib/l3kernel/interface3.pdf. I haven't gotten around to using these things though, and, apparently, these features are still so new you rarely see them referred to in StackExchange answers or Google results.

CXLTX Transform provides the following facilities:

-

\tfFactorMoveX,\tfFactorMoveY: These are scaling factors that will be applied to translations; they're currently defined as\FPmul\tfFactorMoveX{1}{5}and\FPmul\tfFactorMoveY{1}{10}(i.e. 5 and 10), respectively, the idea is to make\tfPushand\tfRaisescale like\prPushand\prRaise(the may change in the future). -

We've already seen

\tfPushand\tfRaise; additionally, there's\tfPushRaisewhich you have to call with anxand ayvalue, analogous to\prPushRaise. -

Scaling can be performed by

\tfScale, which takes two factors. -

The underlying command for all transformations is

\tfTransform, which takes six arguments as detailed above, scales the translations, manages the stack, and performs an arbitrary 2D transformation composed of scaling, translation, and shearing. -

\tfBack, which takes no arguments, undoes the most recent transformation. You can call it any number of time without causing an 'empty stack' exception; it will be called implicitly when the current group ends.

Note Conceivably, CXLTX Transform could be made compatible with LuaTeX by switching between the

pdfliteralandspecialconventions.

Note People who want to implement more transformations should take a look at ftp://ftp.nsu.ru/mirrors/ftp.dante.de/pub/tex/macros/generic/pdf-trans for examples.

CXLTX Style: CJK Glue

CXLTX CJK Glue (CJKG) is, if you will, an ultra-minimal re-implementation of the East Asian typesetting facilities for XeTeX provided by xeCJK.

CJK (sometimes also CJKV to include Vietnamese Chữ Nôm 字喃, 𡨸喃, 𡦂喃) is a convenient label under which the characteristics of the Chinese, Japanese and Korean writing systems are commonly discussed.

When typesetting Chinese or Japanese text, it is important to note that there are no spaces between the kanji, the kana, or the punctuation—not between individual characters, not between words, and not between sentences. (Xe)LaTeX is not prepared for that kind of situation; when no measures are taken, it will try and set arbitrarily long chains of characters without ever detecting any suitable spot for line breaking, leading to ridiculous overflows (or huge gaps in your line when a few kanji appear in the middle of e.g. Western text). Thus, getting the line breaks right is the prime concern when you want to typeset Chinese, Japanese, Korean or mixed text.

In the past, I have mostly relied on the afore-mentioned xeCJK package; but, as I repeatedly went to study the xeCJK manual I was flabbergasted by the sheer amount of material presented, the astounding complexity of the package. The package also introduces quite a few CJK-specific font-related commands,¹ adding to the already somewhat overwhelming array of choices in this field.

¹) e.g.

\addCJKfontfeatures,\CJKfamily,\CJKfamilydefault,\CJKfontspec,\CJKrmdefault,\CJKsfdefault,\CJKttdefault,\defaultCJKfontfeatures,\newCJKfontfamily,\setCJKfallbackfamilyfont,\setCJKfamilyfont,\setCJKmainfont,\setCJKmathfont,\setCJKmonofont,\setCJKsansfont, ...

All told, xeCJK is an ingenious piece of software that can quickly cause

symptoms of a mental 'TeX capacity exceeded' syndrome. If you're

ready to sacrifice the department store for the thrift shop, load your

fonts using run-of-the mill fontspec commands and mark up your CJK text

portions yourself (I do it via code generation...), then CXLTX CJK Glue may be your

cup of tea. From cjkglue-demo.tex:

\documentclass{article}

\usepackage{cxltx-style-cjkglue}

\setlength{\parindent}{0mm}

\usepackage{fontspec}

\newfontface{\fontSunexta}{sun-exta.ttf}[Path=../../jizura-fonts/fonts/]

\newfontface{\fontGaramond}{EBGaramond08-Regular.otf}[Path=../../jizura-fonts/fonts/]

\newcommand{\cn}{\fontSunexta\cjkgUseCjkGlue}

\fontGaramond

\begin{document}

Tea bricks ({\cn 砖茶}, {\cn 磚茶}, zhuān chá) or compressed tea

({\cn 紧压茶}, {\cn 緊壓茶}, jǐnyā chá) are blocks of whole or finely ground black tea,

green tea, or post-fermented tea leaves that have been packed in molds and

pressed into block form. {\cn 紧压茶是为了长途运输和长时间保存方便,将茶压缩干燥,压成方砖

状或块状,为了防止途中变质,一般紧压茶都是用红茶或黑茶制作。}

\end{document}The \cn is an 'environmental' command (one that assumes it is placed inside a

group) that selects a font and instructs LaTeX to use CJK Glue. Specifically, I

chose Sun-ExtA (available e.g. with the Jizura Fonts npm

package), which makes for a

fine default CJK font as it has appealing (and correct!) character

outlines and a near-100% CJK

BMP

coverage. Observe that it is recommended to leave a space between Western

and East Asian text, and that that space should be located in the Western, not the

East Asian text.

CJK Glue does several things:

- It defines a CJK Glue as

\newcommand{\cjkgGlue}{\hskip 0mm plus 0.7mm minus 0.7mm}; feel free to\renewcommandthat definition any time (I think the dimensions should really be relative to font size, but that is not yet implemented). - It makes it so that spaces and newlines are re-interpreted as that glue. This means when you write your CJK text in an editor, you can liberally apply ASCII spaces and newlines without fearing they'll affect the typeset result. The Ideographic Space character (U+3000) remains unaffected and will be treated like any other CJK character.

- Glue is inserted between all characters.

Note that these rules will cause any characters—not only East Asian ones—to

behave like Chinese text: Typesetting English with \cjkgUseCjkGlue will cause

all inter-word spaces to vanish; letters will be distributed more or less evenly

across the lines, and line breaks will occur without hyphens and wherever the

right margin happens to fall. As such, \cjkgUseCjkGlue might in fact prove

useful outside of CJK typesetting.

The re-interpretation of spaces and newlines uses a hack that combines, surprisingly,

an \obeyspaces\obeylines with an \lccode invocation (lc stands for 'lower case'(??wt*??),

and the original code is utterly unparsable to me; a big Thank You goes out to egreg and Marcin Woliński who made this

spell happen).

The handling of inter-character situation takes advantage of XeTeX's

\XeTeXinterchartoks and related commands, as suggested by Leo

Liu, incidentally one of the

authors of the xeCJK package. There are indications that LuaTeX could

re-implement the mechanism in Lua, so this feature might become LuaTeX-compatible

at some point in the future.

Some links:

- ftp://ftp.yzu.edu.tw/CTAN/macros/xetex/latex/interchar proposes macros to make handling XeTeX character classes easier.

- https://www.ctan.org/pkg/xetexref, the XeTeX reference for developers.

- See ftp://ftp.tu-chemnitz.de/pub/tex/macros/xetex/latex/ucharclasses/ucharclasses.pdf for a package that simplifies selecting fonts by Unicode block; this could be a viable alternative to explicit language-by-language markup.

CXLTX Style: AccentBox

CXLTX AccentBox is simply a duplication of an diacritics package authored by A.S. Berdnikov and published as http://www.eutypon.gr/eutypon/pdf/e2000-05/e05-a04.pdf. I does not appear to be included in TeX Live, so that's what i did here. An example:

\documentclass[a4paper,12pt]{book}

\usepackage{cxltx-style-accentbox}

\begin{document}

\textit{Some variations with an asterisk placed above an `i':}

i\upaccent{\tiny *}{\i}i\upaccent{\tiny *}{\i}i\upaccent{\tiny *}{\i}

\textit{i\upaccent{\tiny *}{\i}i\upaccent{\tiny *}{\i}i\upaccent{\tiny *}{\i}}

\end{document}I didn't modify or wrap the original package, so AccentBox does not have a badge like the other CXLTX styles. The commands defined are:

\aboxbar, aboxbase, aboxbaseline, aboxframed, aboxframestepH, aboxframestepV, aboxjoin, aboxmarker,

\aboxnull, aboxrule, aboxshift, aboxsplit, aboxsplitdn, aboxsplitup, akern, baseaccent,

\baseaccentC, baseaccentR, dnaccent, dnaccentbar, dnaccentC, makeaccent, markchar, MARKCHAR,

\marktwochar, nullaccent, nullaccentC, nullaccentR, upaccent, upaccentbar, upaccentC, upaccentL,

\upaccentR. For details please see the PDF linked above; there's also a copy of the manual in the

accentbx folder of this project.

CXLTX Style: SmashBox

Taken from Seroul & Levy's Beginner's Book of TeX (1991), CXLTX SmashBox (badge: sb) provides a

command sbSmash that takes a single argument, boxes it, and sets the box heigth and depth to zero,

thereby preventing it from influencing line height. Alongside with the techniques mentioned in the

TUGboat Article "Removing Vertical Stretch" by Bazargan & Radhakrishnan, 2007,

this may greatly help to keep the layout constrained to a baseline grid, something which can be very

tricky to achieve in LaTeX.

Sometimes, when trying to measure the current position, things don't work out as expected; for example, at

the start of a paragraph, zref-savepos yields faulty y positions because nothing has been typeset yet.

In such cases, \sbDummy may be used; it simply puts a zero-width \makebox into the stream which isn't

visible, but causes the positioning to be 'initialized'. As such, this command is 'not worth the effort',

as its definition is simply \makebox[0mm]{}; however, it's perhaps helpful to name this critter.

CXLTX Style: Convert To

Simplistic unit conversion routine; see http://tex.stackexchange.com/a/37317/28067. Badge is ct; a

single command is defined:

\ctConvertTo{mm}{\the\@paStrutHeight}mmCXLTX Style: Equals

Routines to do equality checks. The badge is eq. Currently, three commands are defined:

\eqTextEquals{$valueOne}{$valueTwo}{if branch}{else branch}

\eqIfTextEqualsThen}{$valueOne}{$valueTwo}{if branch}

\eqUnlessTextEqualsThen}{$valueOne}{$valueTwo}{else branch}\eqTextEquals checks whether $valueOne and $valueTwo are equal strings or expand to equal strings; as

such, it combines the functionalities of \ifdefstrequal, \ifdefstring, and \ifstrequal from the

etoolbox package. If we go and define the following macros:

\newcommand{\cmdA}{sometext}

\newcommand{\cmdB}{sometext}

\newcommand{\cmdC}{othertext}

\def\defA{sometext}

\def\defB{sometext}

\def\defC{othertext}then all of the following comparisons work and will print out OK:

\eqTextEquals{sometext}{sometext}{OK}{wrong}

\eqTextEquals{sometext}{othertext}{wrong}{OK}

\eqTextEquals{\cmdA}{sometext}{OK}{wrong}

\eqTextEquals{\cmdA}{othertext}{wrong}{OK}

\eqTextEquals{\defA}{sometext}{OK}{wrong}

\eqTextEquals{\defA}{othertext}{wrong}{OK}

\eqTextEquals{\cmdA}{\cmdB}{OK}{wrong}

\eqTextEquals{\cmdA}{\cmdC}{wrong}{OK}

\eqTextEquals{\cmdA}{\defB}{OK}{wrong}

\eqTextEquals{\cmdA}{\defC}{wrong}{OK}

\eqTextEquals{\defA}{\cmdB}{OK}{wrong}

\eqTextEquals{\defA}{\cmdC}{wrong}{OK}

\eqTextEquals{\defA}{\defB}{OK}{wrong}

\eqTextEquals{\defA}{\defC}{wrong}{OK}For more details, have a look at The LaTeX String Equality Comparison Primer

Sometimes you need only take some action when string equality tests positively or negatively; in these

cases, you can either call eqTextEquals with an empty true or false branch:

\eqTextEquals{\a}{\b}{true branch}{}

\eqTextEquals{\a}{\b}{}{false branch}or use the equivalent commands \eqIfTextEqualsThen or \eqUnlessTextEqualsThen:

\eqIfTextEqualsThen{\a}{\b}{true branch}

\eqUnlessTextEqualsThen{\a}{\b}{false branch}CXLTX Style: OddEven

cxltx-style-oddeven is a very thin shim for the \ifoddpage command of the

changepage package. It exists to abbreviate the

incantation

\strictpagecheck\checkoddpage\ifoddpage

odd branch

\else

even branch

\fi%to one of these forms:

\oeIfOddPage{odd branch}{even branch}

\oeIfEvenPage{even branch}{odd branch}The advantage of cxltx-style-oddeven is that (1) it always uses the strict option so you don't have

to remember that one, and (2) it uses the more standards-conformant double-brace-pair syntax instead

of the somewhat unusual \if ... \else ... \fi syntax.

CXLTX Style: AbsPos

Sometimes it's useful to make sure where you are on the page in a human-readable

format. In principle you could use the zref package's \zsavepos command for

this, but this command somewhat suffers from using TeX's inhumane scaled points

(of which there are no less than 186449.92 to the millimeter) on the one hand,

and, on the other hand, \zsavepos measures the y coordinate from the

bottom of the paper, not from the top as people do.

cxltx-style-abspos defines two commands: \apToMm and \apSaveXy.

\apToMm lets you convert length literals to millimeters very simply; thanks to

an \usetikzlibrary{calc} incantation you can use simple arithmetic in the

argument, so for example \apToMm{3pt-5in} will print -125.94414mm to the

document.

\apToMm is used by \apSaveXy together with the \paperheight dimension from

the geometry package to calculate the current position (of the top of the

current line), relative to the top left edge of the paper, and write it to a

file named \jobname.cxltx-abspos.txt. You must provide an individual label

for each invocation. Example:

\apSaveXy{label-1}Line 1\\

\apSaveXy{label-2}Line 2\\

\apSaveXy{label-3}Line 3\\

\apSaveXy{label-4}Line 4\\

\apSaveXy{label-5}Line 5\\label-1: (32.38495mm, 33.52794mm)

label-2: (32.38495mm, 41.25996mm)

label-3: (32.38495mm, 45.47743mm)

label-4: (32.38495mm, 49.6949mm)

label-5: (32.38495mm, 53.91237mm)CXLTX Style: TRM

cxltx-style-trm adds color to your console \typeout{}s. Thanks to an ingenious snippet of

code by one Mr. Oberdiek of LaTeX fame, you can now adorn your

diagnostic messages with colors—which sounds like a toy until you get to see the visual improvement that

colorized terminal outputs afford. It's no coincidence that many of the greatest and latest tools in a new

wave of programming—think npm, think homebrew, think git—embrace both the console and colored output.

Prerequisites Run \trmTest to get an overview of the colors and effects available with TRM. Chances

are that on first try, you'll get to see something like this:

^^[[38;05;61m████^^[[0m trmSolViolet

^^[[38;05;33m████^^[[0m trmSolBlue

^^[[38;05;37m████^^[[0m trmSolCyan

^^[[38;05;64m████^^[[0m trmSolGreenThis is because traditionally, TeX is a bit tight on everything that is not strictly a US-ASCII printable character. You'll see a helpful message below the (un)colorized bars that says

In case you cannot see colors above:

====================================

— make sure your terminal is color-capable

(see http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/ANSI_escape_code)

— make sure you're running XeLaTeX with the `-8bit` switch

(other TeXs may or may not work; some TeXs would appear to require

a `-translate-file=natural` or `--tcx=natural` switch)

(now terminating so you can read this output.)

With XeLaTeX, i use the -8bit switch. I generally do not support anything but Unixish OSes with Tex Live

XeLaTeX, so bad luck if you have another configuration and can't make this work. LaTeX is such a complex

beast, i'm always happy when i'm able to connect the dots using a very narrow range of OS and TeX

incarnation choices and have no way to test on other systems. That said, please issue a pull request in

case you feel there's a meaningful upgrade to any given command provided here that can make CXLTX styles

more robust in this respect.

Once you get the test working, you may use e.g.

\typeout{this is \trmIndigo{indigo} output}or similar to get colorful messages onto the console. Each color command switches a color on for the run

of its argument, and terminates output with \trmReset (i.e. switches back to your console base setting).

Not that nesting commands do currently not work the way they should: \trmRed{A \trmBlink{B} C} will

give you a red, static A, a red, blinking B, and a default-colored, static C (instead of a red, static

C). One could fix that but i'm too lazy for that now.

In addition to the colors and effects listed below, there are some convenience output macros:

\trmWhisper{helo} % grey message

\trmWarn{a warning message} % an exclamation mark + message in red

\trmAlert{an alert} % a blinking warning sign + message in redEffects

- trmBlink

- trmBold

- trmReverse

- trmUnderline

- trmNoBlink

- trmNoBold

- trmNoReverse

- trmNoUnderline

- trmReset

Colors

- trmBlack

- trmBlue

- trmGreen

- trmCyan

- trmSepia

- trmIndigo

- trmSteel

- trmBrown

- trmOlive

- trmLime

- trmRed

- trmCrimson

- trmPlum

- trmPink

- trmOrange

- trmGold

- trmTan

- trmYellow

- trmGrey

- trmDarkgrey

- trmWhite

- trmSolBaseOThree

- trmSolBaseOTwo

- trmSolBaseOOne

- trmSolBaseOO

- trmSolBaseO

- trmSolBaseOne

- trmSolBaseTwo

- trmSolBaseThree

- trmSolYellow

- trmSolOrange

- trmSolRed

- trmSolMagenta

- trmSolViolet

- trmSolBlue

- trmSolCyan

- trmSolGreen