Convert a string of terminal output with ANSI escape codes into a

<pre> tag with styled spans (for putting in docs and web

pages), or a flattened ANSI string with normalized color codes

(for use with other ANSI-parsing programs that only support

colors but not control codes).

Colors are supported of course, but so is the full suite of

cursor motion, partial/full erasing, etc. Basically, everything

that ink outputs, it

will resolve and turn into an HTML or flattened ANSI

representation.

import { ansiToPre, ansiToAnsi } from 'ansi-to-pre'

// or however you get a colored ansi code string

import chalk from 'chalk'

const s = `

${chalk.red('red text')}

${chalk.blue('blue' + chalk.bold('bold'))}

`

console.log(ansiToPre(s))

/*

<pre style="background:#222222;color:#eeeeee;position:relative">

<span style="color:red">red text</span>

<span style="color:blue">blue</span><span style="color:blue;font-weight:bold">bold</span>

</pre>

*/Emojis are tricky to work with in JavaScript! Sometimes a single emoji glyph is one character wide, sometimes two, sometimes something in between. Regardless of CSS line-height or font-size, it might be taller than other characters in the line, causing weird spacing that makes your HTML not look like a faithful representation of the ANSI that printed to your terminal.

To address this irregularity, ansiToPre will replace all emoji

characters with an absolutely positioned span, nudged up

0.3ex from its default position, followed by 2 spaces. In my

testing, in most monospace fonts checked, this is about the best

way to make the emoji show up in the right place in the line,

with enough space to be shown fully. Occasionally, for narrower

emojis, this can result in some extra space, but that's usually

better than cutting them off or overlapping other characters.

By default, there are colors assigned to the root pre tag and

the 16 basic ANSI colors, for a relatively basic dark theme.

To change the default colors or the theme, see the theme()

method (and others) described below.

If there's a hyperlink in the ANSI string, using the OSC code

\x1b]8;;<url>\x1b\, then it will be turned into an <a> tag in

the HTML output.

You can also use terminal.setStyle({ href: '...' }) to write

everything from that point forward as a hyperlink, and call

.setStyle({ href: '' }) to stop writing in hyperlink mode.

I needed a way to put the output from tap reports into the documentation, and wasn't able to find an ANSI-to-HTML converter that handled the full set of cursor movements, erases, scrolling, etc. that a complicated ink program outputs. There are several that do colors, and a handful that do the other text styling like bold and underline, but none that handle cursor movement codes. So I was still doing a bunch of manual editing of the files before converting the styles to css, or cleaning up mochibake after conversion. No fun.

I called it ansi-to-pre, because dropping ANSI output into a

<pre> tag is my main use case, but you could conceivably do a

bunch of other interesting stuff with a virtual ANSI terminal, I

guess. You could even use the Terminal class as a sort of

chalk replacement that write to random places in the string of

output, but to be honest, chalk has a much nicer API for most

cases where you just want styled text, and ink is a better tool

for complicated "write stuff to the terminal" tasks.

import {

// main functions

ansiToPre,

ansiToAnsi,

// classes

Terminal,

Block,

Style,

// other goodies

theme,

defaultColor,

defaultBackground,

nameCodes,

codeNames,

namedColors,

namedBrightColors,

xtermCode,

} from 'ansi-to-pre'

Turn an ANSI string into a styled HTML <pre> tag.

Resolve all control codes and return an ANSI color style representation of the result.

A representation of a virtual "terminal" screen where character and style information as the ANSI-encoded stream is parsed.

Important: this is not a full-fledged Stream class. You can

write() to it multiple times, and it will update appropriately,

but it does zero buffering or input validation, so writing a

partial ANSI code sequence will result in mochibake in the

output.

The virtual terminal is an infinitely high and wide screen, with

no scrollback buffer. So, when scrollDown(n) is called (either

explicitly, or with a \x1b[<n>S ANSI code), n lines are

removed from the top of the "screen". When scrollUp(n) is

called (explicitly or via a \x1b[<n>T ANSI code), n empty

lines are added to the top of the screen; the lines lost to a

previous scrollDown action are not restored when scrolling up.

Also, actions that move the cursor down or to the right, which

would on a normal physical terminal be limited to the

height/width of the terminal, are unbounded. For example, on an

actual terminal, echo $'\x1b[1000Bhello' will print "hello" at

the bottom of the screen (unless your screen happens to be more

than 1000 lines high); in this virtual terminal, it will create

1000 empty lines.

Most of the methods (other than toString() of course) return

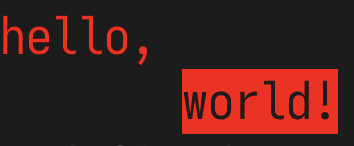

this, allowing for things like this:

console.log(

new Terminal()

.setStyle({ color: '#ff0000' })

.write('hello, ')

.down(1)

.setStyle({ inverse: true })

.write('world!').ansi,

)Outputs:

Create a new Terminal instance. If provided, the string is

written immediately.

A representation of the current state of the Terminal as a

normalized ANSI encoded string. All cursor codes resolved, and

colors normalized to 48;2;r;g;b format.

An array of Block objects each representing a string of text

with a given style.

Returns an HTML representation of the text and styles as a pre

tag with styled span children.

Parse the ANSI encoded string provided, updating the internal character and style buffers appropriately.

Set the style that the terminal will use for text writes.

If a string, must be a valid \x1b[...m and/or

\x1b]8;;<url>\x1b\ ANSI code.

The styles provided will be appended onto the current style in use, just as they would be by a real terminal if the relevant ANSI code is encountered.

Move the cursor up n lines, stopping at the top.

Move the cursor down n lines, without limit.

Prepend n empty lines at the start of the buffer, effectively

moving the cursor up as a result.

Remove n lines from the start of the buffer, effectively moving

the cursor down as a result.

Move the cursor forward n columns, without limit.

Move the cursor back n columns, stopping at the first column.

Move to the start of the n-th next line.

Move to the start of the n-th previous line, stopping at the

top of the screen.

Move to the n-th column (1-indexed), limited by the left-most

column.

Move to the 1-indexed row and column specified, limited by the top and left sides of the screen.

Delete all printed data from the screen.

Note that this is used for both \x1b[2J and \x1b[3J,

because there is no scrollback buffer in this virtual terminal.

Delete all printed data from the cursor to the end of the screen.

Delete all printed data from the top of the screen to the cursor.

Delete the contents of the current line.

Delete printed data from the cursor to the end of the current line.

Delete printed data from the start of the current line to the cursor.

A representation of a run of text in a given style.

Append text to the block

A representation of the block as an ANSI styled string.

The unstyled text that will be written.

The Style object for this block of text.

An immutable representation of an ANSI style. Used by Terminal and Block to represent the styles in use for text to be printed.

If a Style object is created with the same properties as a formerly seen Style object, the same object will be returned.

For example:

const a = new Style({ bold: true })

const b = new Style({ bold: true })

assert.equal(a, b) // passesThis optimization cuts down considerably on object creation,

because a Style is created for each styled character written to

the Terminal buffer. It also means that Style objects can be

compared directly with === to test for equivalence.

Convert a set of properties to an ANSI style code

Convert an ANSI style code to a set of properties

Return a new Style with this one plus the updated properties.

If a string is provided, must be a valid \x1b[...m ANSI style

code, though unrecognized properties within that code will be

ignored rather than throwing an error.

A CSS string corresponding to the style properties set.

True if this style is a full reset of all properties.

A \x1b[...m ANSI code corresponding to this style.

The hex codes set on the <pre> for background and color,

and used as the "unstyled" colors.

Call with a string to change the color used.

Canonical names for the 8 standard colors.

export type Theme = {

defaultColor?: string

defaultBackground?: string

named?: { [name in Names]?: string }

bright?: { [name in Names]?: string }

}A representation of the theme used for the default color and background, 8 standard colors, and 8 bright variants.

Call to get or set the color theme for the default color and background, 8 standard colors, and 8 bright variants.

Returns the theme in use.

For example:

import { theme } from 'ansi-to-pre'

// solarized dark with full-saturation brights

theme({

defaultColor: '#000000',

defaultBackground: '#eee8d5',

// https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Solarized#Colors

named: {

black: '#002b36',

red: '#dc322f',

green: '#859900',

yellow: '#b58900',

blue: '#268bd2',

magenta: '#d33682',

cyan: '#2aa198',

white: '#fdf6e3',

},

bright: {

black: '#586e75',

red: '#ff0000',

green: '#00ff00',

yellow: '#ffff00',

blue: '#0000ff',

magenta: '#ff00ff',

cyan: '#00ffff',

white: '#ffffff',

},

})Mapping of the named colors to their ANSI bitwise grb numeric

color codes. For example, nameCodes.black === 0.

A mapping of the codes 0-7 to their canonical names. For example,

codeNames[0] === 'black'.

Mapping of the named color codes to their HEX color represenations. May be modified to change theme.

Mapping of named color codes to the HEX color represenataions of their bright variants. May be modified to change theme.

This array may be modified to change the color scheme.

Get the HEX code for an XTerm color code between 0 and 255. May be modified to change theme.